A Shift Towards Recorded Interviews

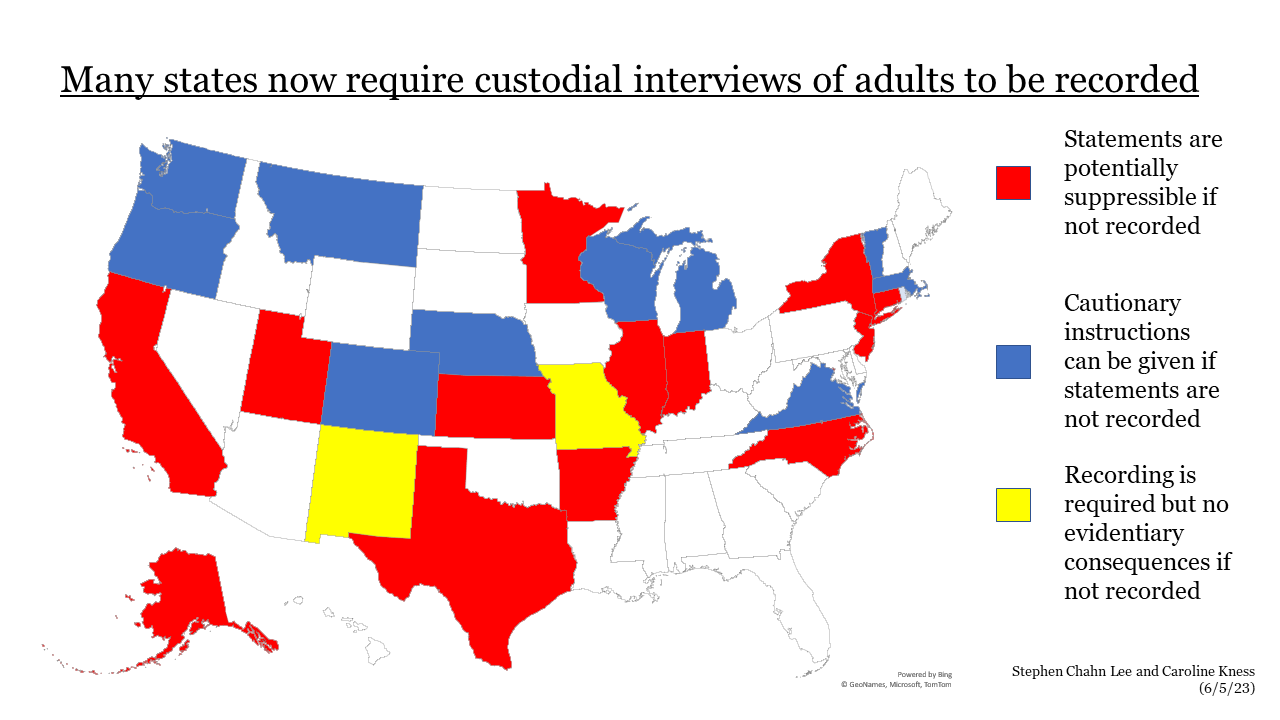

Many states now require law enforcement agents to record some interviews, though the consequences for failing to record varies

Recording devices are now everywhere (including your pocket or purse or hand or wrist), and there have been some big legal changes to reflect this reality. In many states, police now are required to record custodial statements.

In at least 13 states (red in the map), an adult’s custodial statement are potentially suppressible if a recording was not made (state laws differ as to scope, presumptions, and exceptions). Alaska’s Supreme Court led the way on this, with a 1985 ruling that failing to record a custodial interview violated state due process rights.

The main issue, the Alaska Supreme Court said, was not that police necessarily were lying about interviews, but that police definitely were human. The court here quoted the late legal scholar Yale Kamisar:

“It is not because a police officer is more dishonest than the rest of us that we … demand an objective recordation of the critical events. Rather, it is because we are entitled to assume that he is no less human - no less inclined to reconstruct and interpret past events in a light most favorable to himself - that we should not permit him to be a ‘judge of his own cause.’”

New York changed its law in 2018 to require recordings, just a few years after its chief judge noted that there was “no legitimate argument why this best practice should not become universal in the interest of a fair and impartial justice system.”

Many other states (blue), such as Massachusetts, require recordings and specifically allow for juries to be told to evaluate unrecorded statements with caution. Some states (yellow) require recordings but impose no effect on individual cases when police fail to record.

The federal system is not as far along as many states (it effectively would be yellow on the map). U.S. Department of Justice policy since 2014 requires custodial interviews to be recorded, but a violation of this policy has little if any practical effect – prosecutors have still sought and won admission of statements that were not recorded, though at least one federal court has considered giving a cautionary instruction.

Two big issues for practitioners to consider:

First, recording requirements do not apply to non-custodial statements. Law enforcement should consider recording interviews with all suspects and targets, whether or not someone is in custody.

Second, if you are representing a client in an interview that is not being recorded, make a plan to take good notes. I highly recommend having one person specifically designated to take extremely detailed notes of the interview, including (1) memorializing not just the answers but the questions and (2) using exact quotes for any key points. The Meek case (2022 WL 2967716) shows how helpful this can be if there is a dispute.

I decided to look at this after a recent discussion with some other white-collar practitioners in Provisors – hope this is helpful! Thanks to Caroline Kness for her research as well to as Andrew Vail and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers for their work in this area.