How Sherlock Holmes entered the public domain almost a decade ago

Thanks to the case of Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate

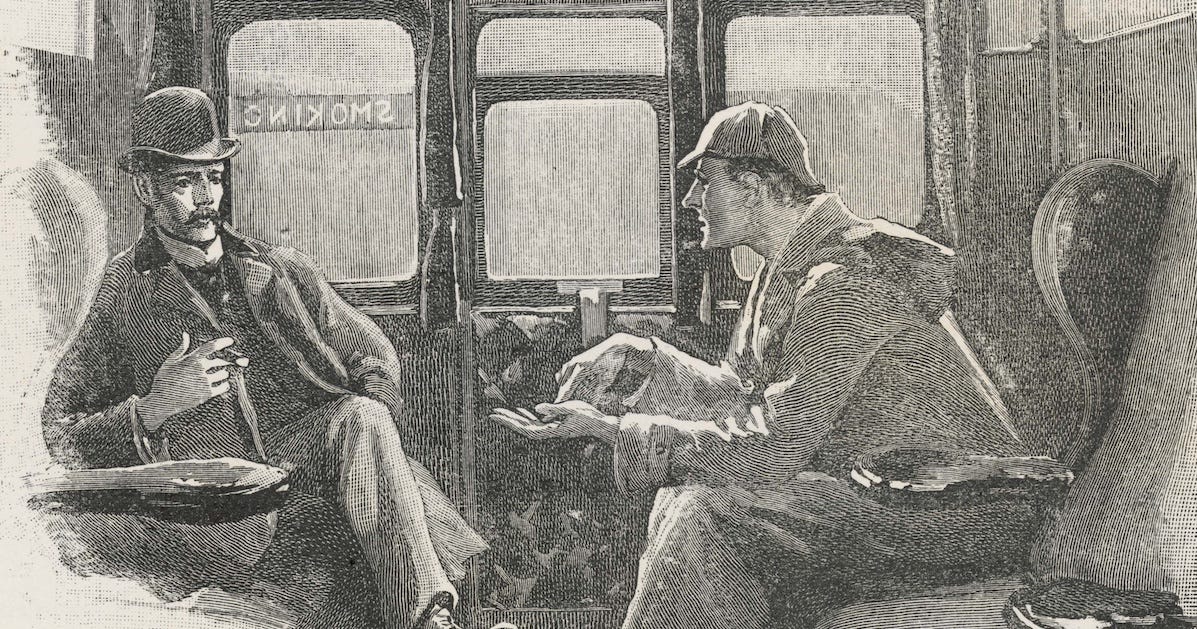

You may have seen articles about how Sherlock Holmes is in the public domain as of January 1, 2023. In fact, almost everything about the character has been in the public domain for almost a decade, thanks in large part to a fascinating court case with some great zingers by Judge Richard Posner.

In 2013, noted Sherlockian and author Leslie Klinger brought a lawsuit against the estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Klinger was seeking to publish a book of short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes and refused to pay the Doyle estate a licensing fee. Anticipating litigation, he initiated a lawsuit against the Doyle estate in the Northern District of Illinois (where the Doyle estate’s licensing agent was located) seeking declaratory judgment.

Most of the Sherlock Holmes stories were already definitively in the public domain, but the Doyle estate argued that the character himself was nonetheless not in the public domain because of the later stories that were still protected by copyright. According to the Doyle estate, Sherlock Holmes was a single integrated work of authorship that was not “complete” until the publication of the later, copyrighted stories.

Federal judges squarely rejected this argument, finding that the character of Sherlock Holmes was in the public domain except for some specific features that originated in the later stories that were not yet in the public domain but which are finally all in the public domain as of 2023.

U.S. Circuit Judge Richard Posner wrote for the Seventh Circuit in 2014:

Only in the late stories for example do we learn that Holmes' attitude towards dogs has changed — he has grown to like them — and that Watson has been married twice. These additional features, being (we may assume) "original" in the generous sense that the word bears in copyright law, are protected by the unexpired copyrights on the late stories.

Minor details, nothing important. And, as Posner went on to say, such "alterations do not revive the expired copyrights on the original characters."

Judges also sharply criticized the Doyle estate’s attempt to seek fees from authors such as Klinger.

Posner wrote in his 2014 opinion that the Conan Doyle estate's attempt to effectively seek 135 years of copyright protection for Sherlock Holmes "borders on the quixotic" in raising the "spectre of perpetual, or at least nearly perpetual, copyright."

He criticized the estate even more in a subsequent opinion that affirmed attorney fees for Klinger.

"The Doyle estate's business strategy is plain: charge a modest license fee for which there is no legal basis, in the hope that the 'rational' writer or publisher asked for the fee will pay it rather than incur a greater cost, in legal expenses, in challenging the legality of the demand," Posner wrote. Posner went on to praise Klinger as a private attorney general who "combat[ed] a disreputable business practice — a form of extortion" and had "performed a public service" for which he "deserves a reward."

Ultimately, Posner's ruling, and rulings in similar cases such as a Second Circuit case involving the characters Amos and Andy, show that characters who appear in stories that are in the public domain as well as in stories that remain protected under copyright can exist in different forms.

There are multiple Sherlock Holmes, and, someday, there will be multiple versions of Darth Vader, as Posner himself suggested in his opinion. Someday, far from now, the Darth Vader who appears in "Star Wars: Episode IV" will come into the public domain before the version of Darth Vader who was Luke Skywalker's father and before the version whose earlier life was depicted in Episodes I through III.

Ironically, the Doyle estate’s attempts to maintain copyright on Sherlock Holmes (both against Klinger and then against Netflix regarding the 2020 Enola Holmes movie) ignored some aspects of Sherlock Holmes himself, as well as failing to recognize the multiplicity of Sherlock Holmes that already existed in the works written by and approved by Doyle himself.

First, the Doyle estate tried to argue that Holmes' friendship with Watson was only created in the later stories, particularly "The Adventure of the Three Garridebs," in which Watson is shot and Holmes is moved. But the Holmes-Watson friendship was not a new feature like the affection for dogs that the Seventh Circuit acknowledged would be protected. Watson and Holmes refer to each other as their “friend” in most of the stories. Holmes referred to Watson as his "intimate friend and associate" in "The Adventure of the Speckled Band" and demonstrated his affection by secretly arranging for Watson's financial success in the public domain story "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder."

And, of course, Holmes referred to Watson as "my dear Watson" in most of the stories, beginning with the novel, "The Sign of The Four."

Second, the Doyle estate's argument ignored the multiple versions of Holmes that existed even within Doyle’s earlier work. Doyle was a brilliant writer, but consistency and attention to canon were not his strong points. The Holmes stories contradict themselves in many ways and have inspired much thinking about who Holmes really is, such as my own “Silent Contest” explanation for why Watson may have intentionally included some lies about Holmes in his stories.

Did Holmes use cocaine or not? No, according to "A Study in Scarlet," the first story, in which Watson says that Holmes had such temperance and cleanliness that drug use would be forbidden. Yes, according to “The Sign of the Four,” the second story, through "The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter." (I lean towards no)

Did Holmes know that the earth revolved around the sun? No, according to “A Study in Scarlet.” Yes, according to later stories showing Holmes with advanced knowledge of astronomy. (I lean towards yes)

And did Holmes love? No, according to most stories, including “A Scandal in Bohemia.” But yes, according to another, less-known story that is credited to Doyle. (I’m agnostic on this one)

1899 saw the premiere of a Sherlock Holmes play written mostly by William Gillette and credited in part to Doyle. The play gave new details about Professor Moriarty and introduced new characters and the phrase "elementary my dear Watson," which never appeared in any of the stories that Doyle wrote on his own.

And, significantly, the play portrayed an emotional Holmes who actually falls in love.

In the play, Holmes helps a female client whose predicament is based on Irene Adler in "A Scandal in Bohemia." At the end of the story, Watson expresses his hope that Holmes and the client may have come to love each other.

Holmes scoffs and recites a passage taken from Doyle's novel "The Sign of the Four": "Love is an emotional thing and is therefore opposed to the true, cold reason which I place above all things. I should never marry myself, lest I bias my judgment."

But Holmes protests far too much. At the end of the play, Holmes himself reveals that his coldly logical side is just a front and that he indeed feels emotions. "I love you," Holmes tells Alice Faulkner. And then they kiss.

Cold or loving, both Holmes existed.

And now, all of us can create our own.

Welcome to the Sherlock-Verse.

About the Author: Stephen Lee is a former prosecutor and former newspaper reporter who has written and spoken about Sherlock Holmes. His analysis of the Holmes stories and why Watson may have lied about certain aspects of Holmes’ life and personality is available as a self-published monograph. He is a solo practitioner in Chicago focusing on health care fraud, data analytics in litigation, and white-collar criminal defense.