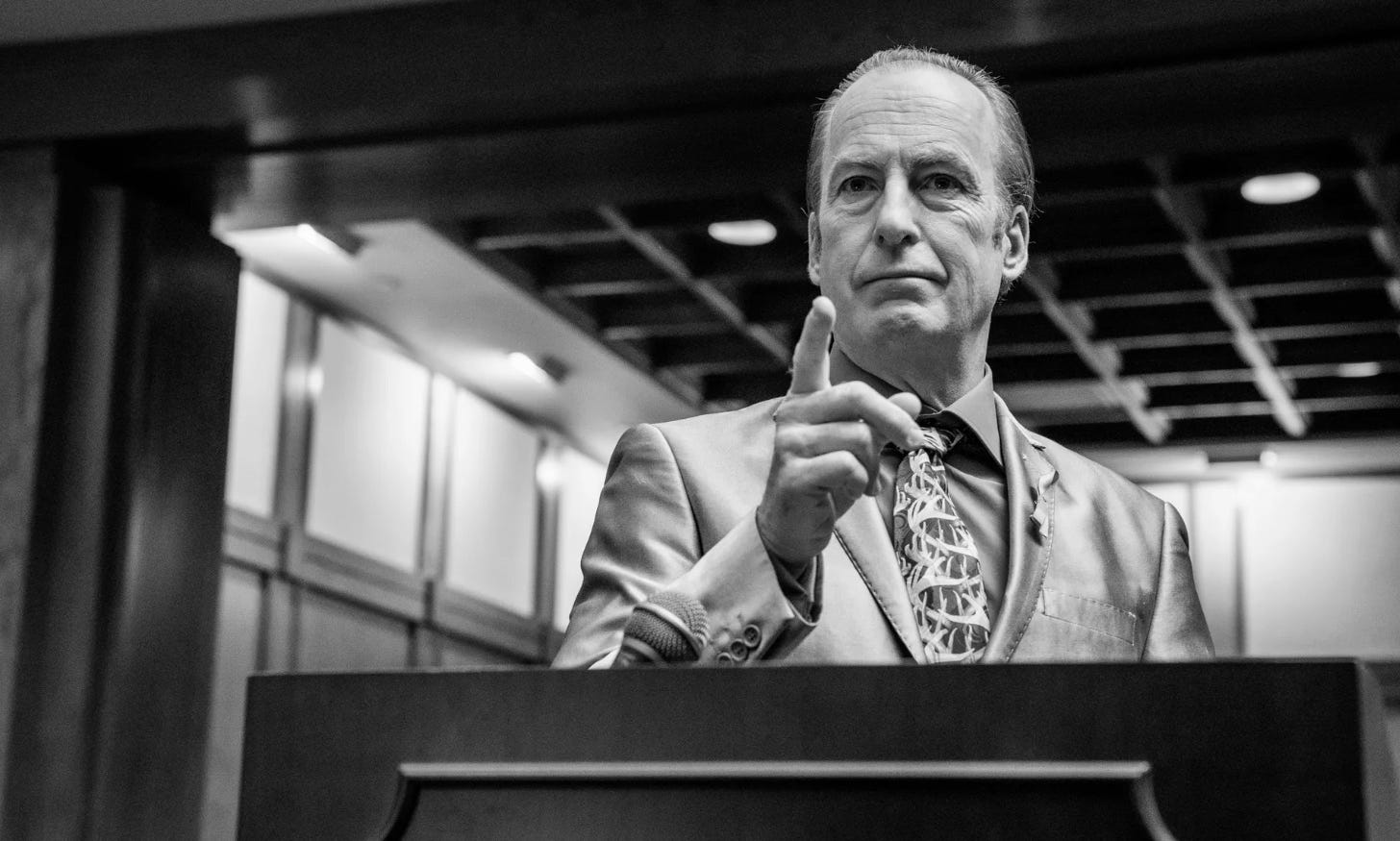

Saul Goodman's Final Defense

Why it worked even if it probably would have been rejected as a matter of law

I finally managed to watch the series finale of Better Call Saul and wanted to share some thoughts. Spoilers below for both Better Call Saul and Breaking Bad!

Give Saul Goodman a lot of credit. He was good at what he did, and his final bit of lawyering was a masterpiece. Unethical and built on a legal argument that he would probably lose, but a masterpiece even so.

Caught after months on the run, Saul faced a strong government case but correctly identified a weak aspect. While the government presumably had built a lot of evidence against him, some of the evidence would be inadmissible and he has the upper hand for a key issue – only he knows what exactly he was thinking when he worked with Walter White and Jesse Pinkman.

So, rather than trying to dispute factual areas where he is weak, he concedes those issues and focuses on the one area where the government could have difficulty contradicting him.

Basically, here’s what he was telling the government:

He would go to trial. This would mean a huge commitment of government time and resources, going after someone who everyone knows was not the main target.

He would testify on his behalf, and he would not deny the conduct that the government has accused him of. This would mean a very different trial than the one that the government might have anticipated when they charged him.

And he would try to make a “duress” defense. Basically, he would argue that he had to commit all the crimes he was accused of because he had no other choice. He would mix real facts (how he met Walter White, and probably Hank’s connections to Walter) with lies, but he had nothing to lose through such perjury. This would introduce legal issues that the government had not expected.

Under the law, if you commit a crime because you are forced to do so, you are excused from criminal prosecution because your crime was committed under “duress” and thus excused. For example, if Kim Wexler really had killed someone because she believed Lalo would kill Jimmy/Saul otherwise, she probably could argue successfully that she did not really have a choice and thus her crime should be excused.

The big legal question would be whether a judge would allow Saul to even make this defense to a jury (via instructing the jury about the defense and how it works).

Courts set a high bar for allowing a defendant to make such an argument as a matter of law. Many people who wanted to raise this defense have not been allowed to do so, such as a man whose teenage daughter was in the physical custody of a man who had abused the daughter and reminded the father that she was “in his hands,” and women who were forced to transport drugs after being raped by their captors and threatened with the deaths of their families.

Ultimately, after lots of public briefing and argument (which would probably make the DEA look bad, given how long it took for Hank to catch onto his brother-in-law), a court probably would not allow Saul to raise the duress defense. Saul could have contacted law enforcement at some point, and he had other means of protecting himself. Even so, such a court ruling would raise the possibility of drawn-out appeals and a chance that a conviction could be overturned.

And even if Saul was prohibited from making the duress argument to a jury, he could still attack a key element of the government’s case with a variation of the defense.

The main charges in a case like this would be conspiracy, probably under Title 21, United States Code, Section 846, and the RICO statute. To convict Saul of conspiracy and RICO, the government would have to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that he had some kind of agreement to commit other crimes.

Proving such an agreement would be tough because the government cannot call any witness or put forth any evidence to prove exactly what Saul was thinking when he worked with Walter White and Jesse Pinkman:

Walter is dead.

Mike is dead and would not cooperate even if he was alive.

Jesse is on the run, and thus his videotaped confession cannot be used at a trial against Saul because (a) it cannot be authenticated, given the death of Hank and Steve Gomez, (b) it would be hearsay, and (c) of the Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause.

People like Francesca or Skyler might help the government, but the government would have no witnesses to contradict Saul’s account of how he first met Walter and Jesse and why Saul kept working with them.

Ultimately, a judge probably would not prevent Saul from testifying in support of there being no real “meeting of the minds” between him and Walter and Jesse, and thus there was no agreement.

All in all, Saul’s play made the government’s case a lot harder and raised the costs of a win.

(And that’s even despite Saul’s cocky line at the end – “all I need is one,” referring to how Saul could win a mistrial if even one juror believes his story. The line suggests that Saul knows that his story is not true, but a jury will probably never hear it. Evidentiary rules generally prevent the use of a statement made during settlement discussions, which the meeting was.)

The government thus was faced with the prospect of (a) a lengthy trial that had some risk of a loss, widespread airing of embarrassing law-enforcement mistakes, and a lengthy appeal even if the government won, or (b) a plea deal that would end the case quickly and that would be acceptable.

Option B sounds a lot better, and that’s how Saul got his deal.

A few more notes on the unusual court proceeding that we see in the final episode:

Before it goes awry, the court proceeding is already an unusual one because it effectively combines two proceedings into one. Usually, in federal court, a judge has (1) a change of plea hearing and (2) a separate sentencing hearing after reviewing more information. But the deal here is for a specific sentence of 7 years that the government and Saul had agreed upon. Under federal rules, the judge cannot accept Saul’s plea without agreeing to impose the 7-year sentence, which is why she has questions for the government about the sentence. And that’s why she asks if Saul has provided “substantial assistance,” as cooperation would be a standard reason for the government to recommend a lower sentence for someone who ordinarily should get a longer sentence.

When Saul makes his statement, he is basically confessing (and preventing himself from arguing duress as he had initially planned), but that’s not the same thing as pleading guilty. It’s unclear exactly what happened afterwards, but that day’s proceeding probably did not end with a conviction or a sentence. He probably did not go to trial, but he probably (1) pled guilty at a later proceeding and (2) was sentenced months later.

He does effectively save Kim from being prosecuted for Howard Hamlin’s murder. Kim had confessed to being involved, but prosecutors cannot prosecute someone based solely on their confession. If Saul had not retracted his statements to the government about Kim’s involvement, prosecutors could have compelled Saul to testify against Kim in a later trial. Saul’s lies and perjury make that nearly impossible.

By the way, as great a scene as it is, the courtroom does seem too empty for a major case. Courts rarely close the courtroom to the public, and nothing about this proceeding would justify that. At the least, there would be multiple reporters as well as more of a law-enforcement presence to see the case wrap up.

A great ending for two great shows. Hope you enjoyed!

I was a federal prosecutor in Chicago for 11 years and was senior counsel to the Chicago U.S. Attorney Office’s health care fraud unit. I worked at two large law firms and recently started a solo practice focused on health care fraud and data analytics. I also used to be a newspaper reporter and was the creator of a news site that reverse-engineered TV shows that ripped from the headlines.